https://sirenassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/a.png

749

1138

Nick Newsom

https://sirenassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/SA-Logo_340156-01-300x138.png

Nick Newsom2022-11-11 07:14:432023-07-27 07:18:14Digital Platform Highlights Importance of Gender Sensitive Approaches to Addressing Cybercrime

https://sirenassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/a.png

749

1138

Nick Newsom

https://sirenassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/SA-Logo_340156-01-300x138.png

Nick Newsom2022-11-11 07:14:432023-07-27 07:18:14Digital Platform Highlights Importance of Gender Sensitive Approaches to Addressing CybercrimeSince June 2021, Siren has been working with a group of seven Jordanian women and three Jordanian men on a community-based participatory research (CBPR) initiative looking at the barriers people face to reporting online blackmail, bullying, sexual harassment and racism. CBPR methodologies aim to get to the heart of community issues by upskilling community members to explore topics that are important to them; by supporting the delivery of practical research findings; and by building trusting relationships among community researchers that can form the basis for action. Here, we hear from Fayrouz, one of the researchers, about how it’s going.

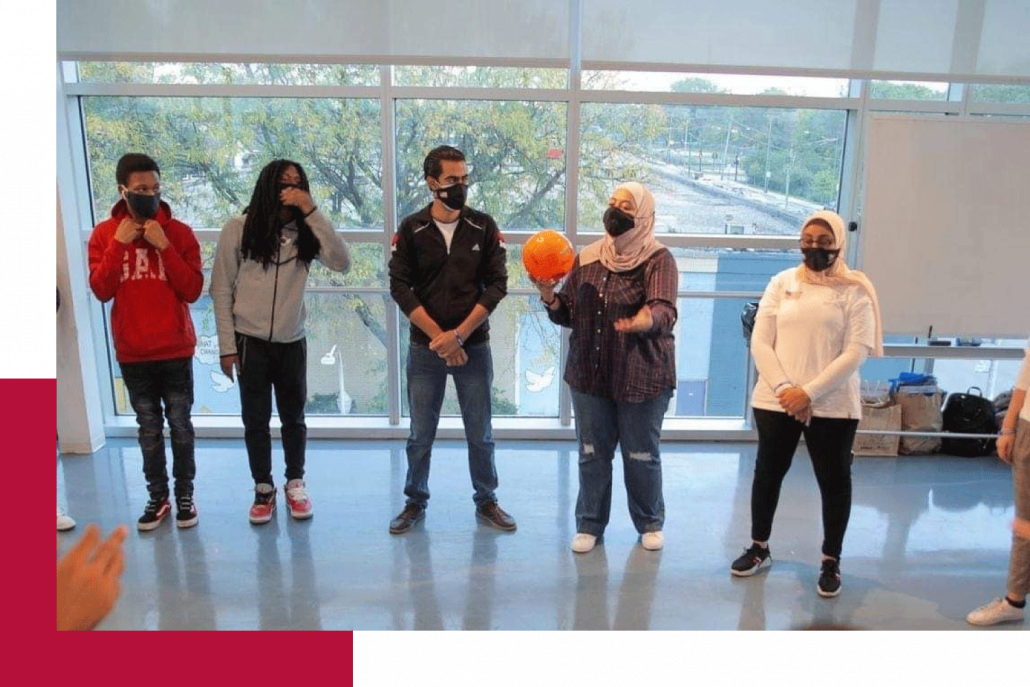

Above image: Fayrouz facilitating a workshop with youth in her local community

8 March 2022

Fayrouz, how did you first get involved in social work?

It all goes back to seventh grade, when I started volunteering at Marka Youth Centre. After a while, I started to hold workshops, teaching and training kids, and doing literacy work. We did activities for all members of society, and I would make sure there was integration of children from different backgrounds, whether Syrians, Iraqis or Jordanians.

What motivated you to participate in this initiative on cybercrime?

I’ve worked with a lot of organisations, and read a lot of research papers, but none addressed this topic well or used this [community based, participatory] method. The idea is to be close to the victims but, in the existing studies, they would only have a paper-based questionnaire, which doesn’t lead to the most credible results. This established my conviction on the importance of the topic, and so I wanted to be a part of this initiative.

Participatory research methods, if done well, can yield higher quality results and serve as a catalyst for action for social change. So, what are the best practices for setting up a collaborative research initiative? Read more

What was the biggest take away from your interviews with cybercrime victims?

Among the interviews I held, the common theme related to ignorance about the procedures for seeking support. In the vast majority of cases, girls knew their rights but did not know how to secure them. They were abused and did not know how to protect themselves. Only a few were able to go to the Cybercrime Unit for help. The rest did not know how easy it is to get the support they need.

Only a quarter of the 76 research participants interviewed by the research team reported the cybercrime they faced to the police. Reporting was significantly lower among refugees than Jordanians, and refugees also confided less in their friends than Jordanians did. Half of the research participants said they were unable to talk to their family to get support.

What did you gain from this experience?

The main thing that helped me change was learning research fundamentals and how to communicate. We had actual communication with victims. Although I’ve collected data before, it was not done in this way. Communicating with victims had a kind of an emotional impact on me, and now I am more aware of the problems surrounding cybercrime.

The next step is networking and raising awareness, including among youth centre managers with the Ministry of Youth, since we know that this problem is present among the girls who visit youth centres.

The research team has identified that a series of dialogue sessions targeting parents and young people should be held as a matter of priority. Their research suggests that the focus of these sessions should be on understanding the nature of cybercrime, as well as the intra-family dynamics surrounding patterns of seeking help and reporting cybercrime.

Where do you see yourself going next?

In the coming years, I’d like to be a researcher-trainer. I love to train people and to communicate. I love to see them reacting to the training, including children and youth. At the same time, I love to read and to research. I am thinking about combining these two. I can work on a research project and come up with a training material design and a full kit out of it. I do not want to let go of either of them.

Since this initiative with Siren, I’ve already worked with Generations for Peace as a researcher. They asked me to join a group of more than twenty school principals and education supervisors to help with assessments and interviews. When I first joined, I thought I was in the wrong place because previously I would always be with volunteers of my age and my university degree. What encouraged them to include me in this work group, regardless of my years of experience and educational level compared to the rest, is my style of work and the ability to analyse and conclude, which I gained through this experience.

Related content

Supported by:

This CBPR initiative is part of Siren’s project “Expanding the Protection Space: Community Safety Service for Displacement Affected Communities”, which is funded by the European Regional Development and Protection Programme (RDPP II) for Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq.